Five things to consider before opening a branch of 'The Bank of Mum and Dad'

Parents have always supported their children in lots of different ways. These days, growing numbers of parents see their adult children struggling to build up enough in savings to put down the deposit on a house or to afford to move up from a first home to something larger - but does this mean parents should help financially?

The purpose of this short guide is to help parents and children to be aware of the main issues they need to consider before going down this route. The purpose is not to put people off but rather to make sure there are no unexpected surprises a few years down the track.

You can navigate through the guide using the table of contents below, or if you'd like to read the guide end-to-end in full, you can download a PDF copy.

- Introduction

- Background - why is it so hard for young people to raise a deposit?

- Deciding whether the money will be a loan or a gift

- Deciding whether you can manage without the money for the long-term

- Understanding the impact of different choices on your tax position

- Thinking through what happens if repayments cannot be made as planned

- Thinking through the consequences of a change in your child’s relationship status

- Other ways parents can help children get on the housing ladder

- Conclusion

Introduction

Understandably, many parents want to do what they can to support their children financially with a house purchase. This could be through a gift, a loan, helping with a guarantee when a mortgage is taken out or a range of other routes.

In this guide, we begin by looking at the challenges faced by young people in trying to build up the deposit on a property in today’s housing and jobs market. We then run through the main factors which parents and children need to consider when deciding whether, and how best to help. While handing over money for a deposit may seem like the obvious solution there are other options and this guide highlights some of the other routes you may wish to explore.

As always, these guides are designed simply to get you thinking and to make you aware of issues that you might not otherwise have considered. But if you are going to make a big financial commitment it is well worth taking independent financial and/or legal advice, as an adviser may well be able to suggest some options you haven’t thought of.

We wish you well as you consider opening a branch of the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’.

Background – why is it so hard for young people to raise a deposit?

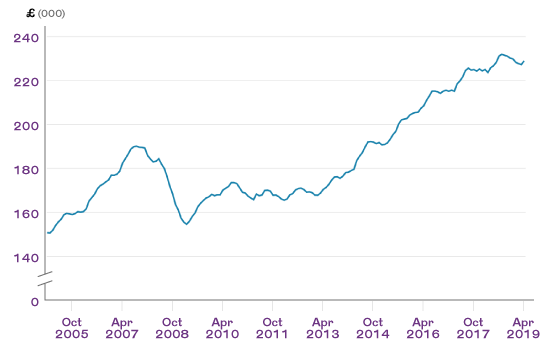

Rapidly rising house prices have put the dream of home ownership out of the reach of many young people. Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show the average UK house price in April 2019 was £229,000i – a whopping seven and a half times the median salary of £30,420ii. The chart following shows how house prices have rocketed in recent years:

Figure 1. Average UK house price, April 2005 to April 2019

The situation becomes worse in cities such as London where average house prices in April 2019 sat at £471,504iii – that's 12 times the average salary in the capitaliv.

With regard to affordability, what matters is not just the total price of the property but also the proportion that is required as a deposit. Until relatively recently, mortgages could be obtained with little, if any, deposit. But a combination of the financial crisis and the subsequent Mortgage Market Review has prompted many lenders to tighten their rules. As a result, the number of mortgage products available at high loan to value ratios fell sharply.

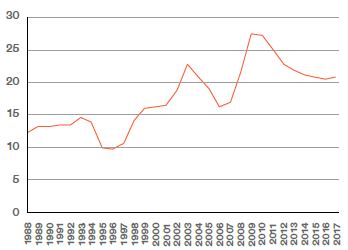

Figure 2. shows the average deposit first time buyers are putting down, expressed as a percentage of the purchase price. While the figure has decreased slightly from the highs experienced in 2009 at the height of financial crisis, it has increased substantially since the 1980s and 1990s.

Figure 2. Average deposit as a percentage of purchase price: First Time Buyers 1988-2017

In absolute terms, the latest English Housing Surveyv found that, in 2016-17, the mean deposit for all recent first-time buyers was £48,591 whilst the median deposit was £25,000. Not surprisingly, the proportion who had help from family and friends – from the so-called ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ – has risen in the last twenty years, from 22% in the mid-1990s to 35% in 2016-17.

Research from the Centre for Economics and Business Researchvi says parents are predicted to lend around £6.5bn in 2017 to help their children get on the housing ladder – a figure that places them alongside the ninth biggest mortgage lender in the UK.

Research from Royal Londonvii shows the extent to which younger generations are relying on the Bank of Mum and Dad for everything from day-to-day living costs to much larger purchases. According to the research 21% of 25-34 year olds regularly receive small amounts of spending/pocket money from parents while 14% say parents regularly pay for every day expenses.

Just under one third (32%) said they had received a lump sum from parents on one occasion while 27% had received lump sums on multiple occasions. Of these, 71% said the lump sum received was for something specific with 54% saying it was to be used to help purchase a property. The money received is clearly needed as 27% said they were not at all confident that they would have been able to save for a deposit without the money while a further third (34%) said they were not very confident they could have done it.

While many parents want to help their children in this way there are potential pitfalls that could have a significant impact on the parents’ financial wellbeing as well as potentially adverse consequences for the parent/child relationship. In the remainder of this guide we run through five key issues that need to be considered before going down this route.

These are as follows:

- Deciding whether the money will be a loan or a gift

- Deciding whether you can manage without the money for the long-term

- Understanding the impact of different choices on your tax position

- Thinking through what happens if repayments cannot be made as planned

- Thinking through the consequences of a change in your child’s relationship status

Disputes can occur when money is handed over without both sides truly understanding the terms. For instance, parents can hand over money believing it is a loan to be repaid over time whereas the child may think of it as a gift that does not have to be repaid.

Royal London research cited earlier shows that only 16% of 25-34 year olds who received money from a parent believed it to be a loan that would need to be repaid. Around two-thirds (67%) said it was a gift while a further 14% believed it to be an advance on their inheritance.

Handing money over without making your intentions clear has the potential to cause long-term harm to the parent/child relationship. Even if both sides understand the money needs to be repaid, if timescales are not laid down then parents can become annoyed if they feel their child is taking too long to pay them back.

What can be done?

Although it may seem extremely formal for a transaction between a parent and a child, setting down in writing what your intentions and expectations are can save a lot of heartache later on. There are two particular reasons why this is a good idea:

- The parents can stipulate how much needs to be paid over what time period as well as whether any interest is due to be paid or not. This means that both parties enter the arrangement with a full understanding of what is expected of them. Get legal help in drafting paperwork if necessary.

- Good record keeping helps with future tax issues. Providing paperwork showing that the money was a gift - and in particular on what date the gift was made - can help in the event of later questions about inheritance tax.

An important issue to be aware of is how the mortgage lender will treat the deposit if it is described as a loan rather than a gift. If the money is a loan then the lender must factor this into their affordability calculations and so may lend less as a result.

Another important consideration when deciding whether to go for a loan or a gift is whether you can afford to do without the money in the long term. We discuss this point more fully in the next section, but if you are planning to hand over the money as a gift, you need to think through what would happen if your own circumstances were to change. Perhaps you can afford to do without the money now, but might you need it later? Similarly, even if the money is a loan and you expect it to be paid back, what impact would it have on your lifestyle if repayment was delayed for some reason?

Lending or giving away a substantial lump sum towards a house deposit may seem like a good idea in your current situation, but people’s circumstances can change quickly. The sum of money handed over may not be needed now, but what happens if life subsequently becomes a bit of a struggle?

Before making the decision to hand over money it is worth thinking whether your finances are able to withstand any of the following major life changes:

When grandchildren come along

While your children may be able to afford to make repayments in the beginning it may be worth considering what might happen if and when they have children. The cost of maternity leave, childcare and schools can eat into your children’s budgets and mean that what was once an affordable loan for them to repay can become difficult to service. If you are dependent on the regular repayment of the loan, this could create real family tensions at what should be a particularly happy time.

Later life costs

You may be fit and healthy now, but what would happen if you or your partner needed to pay substantial care bills later in life? Research by Knight Frank for the 2018-19 financial year put average weekly nursing home fees at approximately £897viii.

Care within the home can also eat into your income. An hour of care each morning and each evening at a cost of £15 per hour would cost nearly £11,000 a year, and many people are supported by home carers for many years. There is also the potential for extra costs for home modifications if mobility is affected by health conditions later in life.

All of these costs can very rapidly eat into your savings and if you have stretched yourself to the limit to help your children, what would happen if you were the one who needed the help?

It is difficult to get people to engage with the issue of long-term care as no one wants to think of a time when they might be unable to look after themselves. Royal London research shows it is not an issue that people prepare for. In a recent survey, only 22% of 65-69 years olds said they had considered how they would pay long-term care costs while only 6% had taken action. Even at the 70-74 age group only 24% said they had considered how to fund these costs and only 7% had taken any action on it.

Changing working patterns

When making choices about how much we can afford to make available to our children we may make assumptions about our current employment and how long it might last. But ill health could have a major effect on the length of your working life and your earnings potential. If affected by ill health or caring responsibilities you could find yourself working fewer hours, changing roles or even leaving the job market altogether before you reach retirement age. You could easily find that you are managing on less money than you had expected, and possibly at relatively short notice.

Your other children

Your children may have a keen sense of ‘fairness’ when it comes to the financial support that you give to each of your offspring! Even if one of your children seems well settled and established in the housing market while another seems to need more help, it is worth bearing in mind that things can – unfortunately – change. The one who seemed settled could experience relationship breakdown, job loss or ill health and may even end up back in the family home – the so-called ‘boomerang generation’. In working out how much you can afford to give to a child in current need, it would be wise to consider all eventualities and potential calls on your support from other family members.

Divorce

Not a happy subject to think about, but it is a fact that the number of people divorcing later in life is higher than in the past. ONS statisticsix show that in 2018 8,570 men over the age of 60 got divorced while 5,725 women over the age of 60 did the same.

This compares to 5,889 and 3,290 respectively back in 1998. If you have planned to support your children based on a joint financial future with your spouse, things could look very different in the unhappy event of a marriage breakdown, and you may want to think if your financial provision for yourself would look as robust in that case.

There are several potential tax issues that need to be considered before deciding to make a gift to support a house purchase.

Inheritance tax

If you gift money for a deposit to your child then there is no tax to be paid on it immediately. However, if the money is handed over as a gift then there is the potential that an inheritance tax liability could be incurred if the giver were to die within seven years of making the gift and their estate is worth more than the inheritance tax threshold (currently £325,000x). In other words, even though the money has been handed over, some or all of it could still count towards the estate of the giver if they were to die.

There are several gifting allowances that can be utilised. As it currently stands you can give away up to £3,000 of your income each year without it potentially counting towards the value of your estate. In addition, gifts of up to £5,000 can be made to help with a child’s wedding. You can also make unlimited small gifts of less than £250 to as many people as you wish without incurring inheritance tax. Please note this is a £250 limit per person.

However, for gifts in excess of this amount then inheritance tax of up to 40% will be payable if you die within seven years of making the gift. Keeping a record of any gifts made will be helpful2.

If you wanted to make gifts on a regular basis then you can use the “normal expenditure out of income” approach. To do this the giver must undertake to make the gifts regularly and the money must come from income, as opposed to capital. Most notably making the gift must not lead to deterioration in the giver’s standard of living. Again, it is important to document these gifts.

If you become a joint purchaser of a property with your child then your share of the value of the home will count towards the value of your estate for inheritance tax purposes when you die. If there were to be an inheritance tax bill when you die, it would be difficult for your child to use this part of their inheritance to pay any tax bill, so you may wish to ensure that more ‘liquid’ resources could be found elsewhere in your estate to pay any such bill.

Stamp duty on second homes

If parents buy a property with their child and are named on the deeds while already owning a property, they will be charged the higher rate of stamp duty which applies to purchases of second homes. Simply helping your child out with a gift of a deposit will not incur this charge, nor will acting as a guarantor on the mortgage.

For those in this situation the stamp duty on second homes worksxi as follows:

- Properties costing up to £125,000 will incur a stamp duty of 3%

- Anything between £125,000-£250,000 will incur stamp duty of 5%

- Anything between £250,000-£925,000 will incur stamp duty of 8%

- Anything between £925,000-£1.5m will incur stamp duty of 13%

- Anything over £1.5m will incur stamp duty of 15%

The situation in Scotland is different as stamp duty was replaced by the Land and Building Transaction Tax (LBTT) in 2015. There is still a tax to be paid on second homes but the rates are different as follows:

| Existing LBTT | Additional home supplement | |

| Up to £145,000 | 0% | 4% |

| £145,000-£250,000 | 2% | 4% |

| £250,000-£325,000 | 5% | 4% |

| £325,000-£750,000 | 10% | 4% |

| Over £750,000 | 12% | 4%xii |

Income tax

If parents choose to lend money to their children and charge interest then income tax would need to be paid on the interest received. If this is the case then a self-assessment tax return would need to be completed each year.

However, there are allowances available that you can claim. The Personal Savings Allowance means basic rate taxpayers can earn up to £1,000 in savings income tax free. Higher rate taxpayers can earn up to £500 in savings income tax free.

Capital gains tax

If the support of the parent is in exchange for ‘taking a share’ in the property and it is then sold at a profit then capital gains tax may be payable. Capital gains tax needs to be paid if a second home is sold at a profit that is more than the current threshold (known as an annual exempt amount) which is £12,300 for the 2020/21 tax year.

The amount of tax due would depend on the share of the property which was owned by each party. For instance, if a parent handed over a 10% deposit at the time of purchase and the property was sold at a profit then they would have to pay capital gains tax on that 10% share in the profit generated.

To work out the gain you need to take the sale proceeds and then subtract the costs of buying the property. This includes the purchase price as well as any stamp duty and legal fees that were incurred. The costs of selling the property can also be subtracted - for instance legal fees and estate agent fees. The cost of major improvements can also be deducted. Once these deductions have been made then the gain can be worked out.

If you are a basic rate tax payer you will pay 18% capital gains tax while higher rate tax payers will be charged 28%xiii.

If you lend money to your children and agree a schedule of repayments, it is important to think through the risk that they may, through no fault of their own, find that they cannot keep up with the repayments. There are a number of issues to consider.

Long-term absence from work

Even if both parties understand that money has been handed over as a loan that needs to be repaid there can still be problems. You may find that your child has no issue initially with making the repayments but then they could lose their job or spend time out of the workforce due to long-term illness and find that making the payments becomes a problem.

Such a situation can put considerable strain on the relationship, particularly if your child doesn’t tell you what is going on straight away. Parents may find themselves under increased financial pressure as a result. Ask yourself in advance if you can afford to meet your own financial commitments if this were to happen and also encourage your child to talk to you if they are experiencing any difficulties.

Your child can protect against such a situation by having an income protection policy in place. The level of employer support for long-term sickness absence can vary widely so an income protection policy can be very useful in that it pays out an income until your child is able to return to work.

Royal London’s State of the Protection Nation report showed that while UK adults recognise the need to have protection in place very few actually take it up. Having income protection in place to protect against such an outcome can offer some degree of comfort.

Negative equity

House price growth has been strong for some time and more people are stretching themselves to get a foothold on the housing ladder. This is often done with the expectation that house price growth will continue and the property can be sold at a profit. However, what happens if we see a housing market crash? If people have stretched themselves to the limit they may find themselves in negative equity.

While this isn’t immediately an issue if your children are still living in the home, what happens if the home needs to be sold quickly due to a divorce or job move? There is a chance the property could be sold at a price that means your child is unable to repay the money you loaned them. Again, when deciding whether to lend money for a deposit it is worth considering how you would cope financially if that money were not to be returned.

At a happy time when a child is setting up home for the first time with their spouse or partner, it is hard to think about the possibility that the relationship may not last. But thinking about such things ahead of time can influence the way that you set up any financial support and can make things easier if the worst should happen.

‘Joint tenants’ or ‘tenants in common’?

Properties can be held in different ways. Holding a property as joint tenants (also known as beneficial joint tenants) means that both parties hold an equal share in the property and, if sold, they will take an equal share of any profit. However, property can also be held as tenants in common. This allows each co-owner to specify their share in the property so once sold each partner receives their share.

If your child is purchasing a home with a partner and you have contributed towards the deposit then it is worth considering whether the property can be held as tenants in common. They can speak to a solicitor about getting something called a “Declaration of Trust beneficial interest” in place. This is a legally binding agreement that clarifies what each person pays towards deposits/fees/mortgage payments. Should your child then split with their partner then there is a legal record of who has paid what.

Cohabitation agreements/Prenuptial agreements

Again, not the easiest conversation to have, but in some cases an agreement between the members of an unmarried couple about what happens if things don’t work out can save heartache later. This could be a cohabitation agreement or, if due to get married, a prenuptial agreement.

Even if the property is in your child’s name and a partner subsequently moves in there is a chance they could still acquire rights to the property. In such a case a cohabitation agreement could prove useful in highlighting who owns what, the financial arrangements made while living together and how assets and property should be apportioned in the event of a breakup. Again, it is worth speaking to a solicitor about how to draft the documentation.

In this article, we have assumed that parents are simply gifting or lending money to their children from their own financial resources. But in many cases the parents will have more in the way of housing wealth than ready cash, and so may need to find a way to tap in to their own housing equity in order to help their children.

Alternatively, parents may not have access to a large lump sum but may be able to help their children with regular saving towards a deposit over a number of years. In this section, we consider some of the ways in which this could be done. In all cases, a financial adviser would be able to offer more information and would be able to suggest the best strategy in your individual situation. Options include:

Opening a Lifetime ISA

Since April 2017 anyone between the ages of 18 and 40 has been able to open a Lifetime ISA (LISA). This product is aimed at helping people either purchase their first home or save for retirement. The maximum that can be contributed is £4,000 per year and in return the government will top it up with a 25% bonus.

Such an offer could prove tempting for parents wanting to help their children save for the long term in a tax-efficient manner. Gifts of up to £3,000 of your income (not capital) can be paid into a LISA every year without risk of incurring an inheritance tax charge. If you want to stretch to the whole £4,000 per year then be aware of the fact that it could attract an inheritance tax charge if you die within seven years of making the gift and your estate is worth more than the inheritance tax threshold.

Equity release

If you do not have much ready cash available but do have a lot of wealth tied up in your house then you might be able to access a cash lump sum for your children through an ‘equity release’ product. How much you can release depends on your age as well as the value of your property. There are two main sorts of equity release products:

- Lifetime mortgage: this is by far the most popular form of equity release; under this approach, you continue to own your property but take out a new mortgage secured on the property; you can make regular repayments as with a more traditional mortgage or you can simply let the interest ‘roll-up’. If you die, move into long-term care or sell the property the loan amount and any interest has to be paid.

- Home reversion: with this approach, you sell part or all of your home to a provider in return for a lump sum or regular payments. You have the right to continue living in the property until you die, rent free, but you have to agree to maintain and insure it. At the end of the plan your property is sold and the sale proceeds are shared according to the remaining proportions of ownership.

Interest rates on equity release products can be higher than for regular mortgages and you should definitely seek advice before taking out such a product. An adviser can also look at whether using the value of your home to act as a guarantee on your child’s mortgage might be a better idea.

Second charge mortgages/remortgaging

Parents can remortgage their property to release capital to lend to children. This can be done with your current lender or by moving to another one. However, if you will be repaying the loan into your retirement years then the lender will want to make sure you can service the payments. Getting a mortgage has proved difficult for those coming up to retirement. However, there has been a shift in attitude in recent years with lenders such as Nationwide offering mortgage products for borrowers up to age 85 and over.

However, if high early exit fees have put you off remortgaging then a second charge mortgage could be another option. A second charge mortgage allows borrowers to use the equity in your home as security against another loan. This means you have a second mortgage on your home but you could be paying lower interest rates than you would if you had an equity release policy. Of course, parents need to be confident they can service the mortgage payment and a lender will want to check this carefully. It is a decision that should be made carefully and on the basis of impartial advice.

Acting as a guarantor

An increasing number of mortgage deals allow parents to act as guarantors on their child’s mortgage or else have their savings used as security. The idea behind such products is that because the purchaser has increased financial backing the lender is able to lend more, often at a lower interest rate than would otherwise have been the case. The two main types are:

- guarantor mortgages, which enable a parent or family member to guarantee the mortgage repayments. This means that if a payment is missed then the guarantor will have to cover the cost;

- family deposit mortgages, which allow a family member to deposit money into a savings account where it is held for a fixed period as security. During this time the money still earns interest but if the borrower defaults the money will be taken from the savings account.

Such products can prove really useful in giving a child a helping hand on to the property ladder and can seem attractive to parents as they don’t have to hand over money upfront.

However, you should beware if your child has had previous issues with handling their own money. If they default on the mortgage then you are liable - can you afford to do that and meet your own financial commitments?

Even if the property was to be sold as a result of non-payment, parents may find they sit far down the list of creditors that need to be paid so may get very little of their money back.

Conclusion

The mix of rising house prices, high student debt and a challenging job market means it is becoming increasingly difficult for young people to save the money needed to get a step on to the housing ladder.

While parents may wish to assist their children in terms of helping out with a deposit or even jointly purchasing a property it is important to be aware that circumstances can change and the decision to hand over money could result in severe financial hardship for the parent and/or place the relationship with the child under considerable stress. In addition, unexpected tax bills can be a cause of great stress.

Much of this potential hardship could be averted if provisions are put in place. Thinking ahead, being clear about your intentions and seeking legal and financial advice where appropriate means many common misunderstandings can be avoided. This guide has also highlighted that there are many other options to helping children fund a house purchase than handing over a lump sum as a deposit. Considering such options means the Bank of Mum and Dad can continue in business for many years to come.

Disclaimer: This paper is intended to provide helpful information but does not constitute financial advice. Originally issued by The Royal London Mutual Insurance Society Limited in July 2017 and last updated in April 2020. Information correct at that date unless otherwise stated. The Royal London Mutual Insurance Society Limited is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority. The firm is on the Financial Services Register, registration number 117672. Registered in England and Wales number 99064.Registered office: 80 Fenchurch Street, London, EC3M 4BY.

Footnotes

i - Source article

ii - Source article

iii - Source article

iv - Source article

v - Source article

vi - Source article

vii - Source article

viii - Knight Frank 2019 Care home trading performance review.

x - Source article

xi - Source article

xii - Source article

xiii - Source article

1We are assuming for now that the parent already has access to a cash lump sum and wants to help fund a deposit more-or-less immediately. Later on in this report we look at ways in which parents can help their children to save for a deposit over the longer term and also at ways in which parents can tap in to their own housing wealth in order to help their children.

2Gifts made 3 to 7 years before your death are taxed on a sliding scale known as ‘taper relief’. For gifts made less than three years before a death, the full IHT rate of 40% is payable. Between 3 and 4 years the rate is 32%, between 4 and 5 years 24% and so on down to zero after 7 years. You can find out more at https://www.gov.uk/inheritance-tax/gifts