Of all the things that cross your mind in the run up to having children, it’s fair to say that the impact on your finances will not be the thing you wish to dwell on. But how you plan to manage your money both before and after the patter of tiny feet should be a consideration once you’ve decided you’d like to start a family.

Children are amazing – and expensive. And the hardest thing is bearing the extra household costs with – often – a decline in household income. In order to be prepared and avoid some scary surprises – like the cost of childcare (hint: it’s eye-watering), you need to know some facts about what is likely to happen to both your outgoings and your income and some ways to manage this.

That’s what this guide is all about. It will hopefully give you enough information to know what you are letting yourself in for – so that when your family goes from two, to three to four or more – you are a little more prepared, and can concentrate on the important stuff.

You can navigate through the guide using the table of contents below, or if you'd like to read the guide end-to-end in full, you can download the PDF.

Introduction

This guide is designed to help aspiring first-time parents with their financial planning.

It explains why having and raising children can be such a financial challenge, gives details of the biggest financial pain points you will probably go through as a parent, and offers some suggestions for how to manage them.

Topics covered include:

- The big picture: the way that starting a family generally causes your outgoings to rise and your income to fall at the same time – something we have called the ‘Concertina Effect’

- Six financial ‘pain points’ to be aware of when starting a family and as your family grows

- Four golden rules for making a Family Financial Plan

Increased costs

Never in your life are you likely to be as financially stretched as when you start a family. In fact, when childcare costs are taken into account, young families are one of the groups most at risk of living in poverty.

Children are an expensive business, not just at the beginning of their lives, where new parents are likely to be most focused, but for the long haul.

The ‘basic’ cost to a couple of raising one child to the age of 18, excluding the cost of childcare, is estimated to be around £75,000, or just over £4,000 a year, according to the Child Poverty Action Group. With childcare costs and additional housing costs included, the ‘cost of a child’ doubles to £8,000 a year.

On that basis, if you start your family at the typical ages of 29 for a new mother and 33 for a new father, and if you have an average joint disposable income of around £34,000 for earners in that age bracket, then this extra £8,000 year equates to getting on for a quarter of your disposable income to cover the extra cost of your first child, though extra tax breaks and family benefits may help to ease the pain.

Just keep multiplying that figure by the number of children you want to have for an estimate of the extra money you may need to find over the years, and you can see how you can quite quickly go from “doing ok, thanks very much”, to counting the pennies.

Generally speaking, the expense is highest in the early years of your child’s life, particularly if you have childcare costs to contend with. Depending on your plans for schooling and for how much of a leg up you want to give them with their finances in later life, you can expect the costs to level out a bit over time.

This weighting of costs towards the early years means a little planning before you start a family could go a long way towards preventing you struggling financially once you become a parent.

Reduced income

It’s not just the cost of feeding and clothing children that has a big impact on the finances of a first-time family, it’s the likely drop in household disposable income as well. You are likely to experience this in two ways:

- Even with the most generous employer, parental leave is unlikely to offer you full pay for the whole of the first year. For much of that period you could find yourself on a reduced income or even with no income at all. We discuss the rules around pay during parental leave later in this guide.

- You cannot simply assume your income will go back to where it was once parental leave is up. The logistics of working in exactly the same way as you did before can be difficult. Many parents find that at least one partner has to work part time for a number of years in order to fit work around drop offs and pick-ups of children.

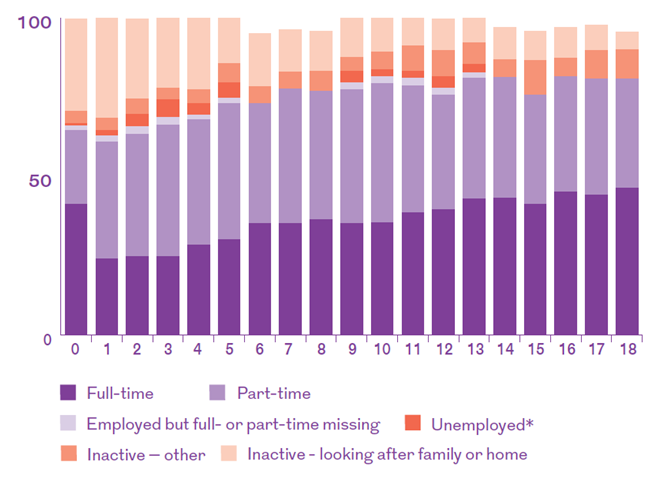

Official figures from the Office for National Statistics show that the most common working arrangement among couples with children is for the father to work full-time and the mother to work part-time until the youngest child is 11.

This chart shows work patterns for mothers by their youngest child’s age (bear in mind that in some cases these women will already have another older child at home, which explains why fewer than might be expected are working full time at the beginning).

The significant rise in costs, together with a drop in income, gives rise to something we have called “the concertina effect” – a double hit on parental living standards as costs go up and income goes down. This squeezes the disposable income of parents significantly compared to the amount of spare cash they had before children.

Source: Labour Force Survey. Note that columns do not always sum to exactly 100% owing to data gaps in the original ONS data.

We don’t want to put a dampener on the excitement of preparing to start a family! But it’s worth being prepared for some of the financial pain points you can expect to encounter, not least so that you can plan ahead and they won’t be so painful.

PAIN POINT 1: The drop in income during parental leave

The extent of the financial pain you feel during the first year of your child’s life depends on whether you are employed, self-employed or unemployed. If you are employed, a key factor is the generosity (or otherwise) of the parental leave package from your employer

(and your partner’s employer if applicable).

If you are planning a family and in employment, the first step is to check the parental leave policy in your contract – and your partner’s contract. If you can’t find your contract, then contact your HR department (or person) for a copy.

For most parents, whatever their employment status or parental leave policy, income is likely to fall during the first year of a child’s life by anything between a quarter and three quarters of whatever was normal in the ‘BC’ years.

We’ve given examples below with different parental leave options to demonstrate the huge pounds and pence difference this can make to you. All examples are based on 2019/2020 rates.

Maternity Allowance

The first two examples cover those who are self-employed or unemployed when they have a child and who therefore do not qualify for maternity pay from an employer. In this case, the main help available is a benefit called Maternity Allowance. The amount you get depends on your record of National Insurance Contributions. For those with Class 2 (self-employed) National Insurance contributions for at least 13 of the 66 weeks before the baby is due the rate is £148.68 per week, but otherwise the rate is just £27 per week.

Case study 1: A self-employed mother

Type of support: maternity allowance

Full amount (in 2019/20) = £148.68 a week for 39 weeks.

A total of £5,798 for 9 months, or £639 a month.

Not paid enough Class 2 National Insurance Contributions?

You get just £27 a week for 39 weeks, or a total of £1,053 for the duration of your leave.

If you are used to earning around £20,000 a year from your self-employment, or roughly £17,000 net of tax and national insurance, even the full rate of maternity allowance comes in at barely a third of that.

Case study 2: An unemployed mother

Type of support: maternity allowance

Maximum amount = £148.68 a week for 14 weeks.

A total of £2,081 for the first three months, or £639 a month for three months and one week.

You can get maternity allowance for 14 weeks if you were employed for at least 26 weeks in the 66 weeks before your baby is due and you are married or in a civil partnership, and you are not eligible for Statutory Maternity Pay from a job. The full eligibility criteria and a calculator for Maternity Allowance are on the government website at www.gov.uk/maternity-allowance/eligibility

Statutory Shared Parental Leave

For parents who are in work but do not benefit from any additional employer parental leave there is a statutory entitlement to ‘shared parental leave’ as set out in the following example. As shown, the best approach to take can depend on which member of a couple is the higher earner and whether one or other partner has access to something better than this statutory minimum.

The benefit with shared parental leave is that a higher earning mother can return to work sooner and the couple still benefits from some sort of statutory pay for the stay-at-home parent.

However, because maternity pay tends to be more generous than shared parental pay or paternity pay, most couples are still better off if the mother takes the most time out of work and the father returns to work.

It’s important to take into account your partner’s earnings and benefits as well as your own when deciding what is best.

Case study 3: An employed parent (mother or father) without an employer parental leave pay package

Type of support: statutory shared parental leave

Full amount = £148.68 a week for 37 weeks (or 90% of the employee’s average weekly earnings if lower).

A total of £5,501 for the full 37 weeks or £611 a month for nine months, shared between the parents, with one returning to work and earning normally for some of the time.

You can share 50 weeks of leave, but receive only 37 weeks of pay, in the year after your child is born.

Or

Statutory maternity leave

Full amount = £148.68 a week for 39 weeks (or 90% of full time earnings, if that is lower).

A total of £5,798 for the full 39 weeks, or £644 a month for nine months.

Employer paternity leave package

As shown in the next example, statutory provision for new dads who want to take time off work following the birth of a child can be very limited.

Case study 4: An employed father with a standard employer paternity leave pay package

Type of support: paternity leave

An underwhelming two weeks on full pay once the baby is born is normally offered.

However, the statutory minimum is £148.68 a week for two weeks (or 90% of full time earnings, if that’s lower).

Employer maternity leave packages

In addition to the statutory minimum level of maternity pay, many workplaces offer an enhanced package but this varies considerably from workplace to workplace, as discussed below.

Case study 5: An employed mother with an employer maternity pay package, earning £25,000 a year

Type of support: enhanced maternity leave

The full amount depends on the employer, but it is usually more generous than statutory pay. According to a survey by ‘XpertHR’, more than 50% of employers offer a package more generous than the legal minimum.

Maternity pay is usually significantly more generous than paternity pay.

A typical maternity pay package might be one of the following:

- Full pay for six weeks, followed by 33 weeks of statutory pay = £7,790 over the 39-week period

- Full pay for six weeks, followed by a lower level of enhancement (eg half pay for 20 weeks), then statutory = £9,623 over the 39-week period

-

Paying more than six weeks at full pay

(eg. 3 months) followed by statutory maternity pay (most common) = £10,115 over the39-week period

-

Paying full pay for more than six weeks (eg. Three months) followed by a period at a lower rate of enhancement (eg three months’ half pay) = £11,159.16 over 39 weeks.

In all of the above examples, it is clear how much of a hit parents can take in the first year of their child’s life on their joint household income.

If you are thinking about changing jobs before you start a family it is worth bearing in mind that large employers tend to be the most generous when it comes to paying you during periods of maternity absence.

And public sector organisations are more likely than private to offer enhanced maternity leave, according to XpertHR.

However, you usually have to have been employed for a minimum of six months before you become eligible for maternity or paternity leave pay.

To give an idea of why you need to save and budget carefully in preparation for that first year, take a look at the schedule of pay for someone on £25,000 a year who takes a year of maternity leave with three months’ full pay, three months’ half pay and six months no pay.

In this example, the total of £8,139 over the year compares with normal net pay of £20,532 – this is a massive £12,393 less than you would normally earn in a year.

If trying to budget for that blows your mind, add up all of the months’ pay over the year of maternity leave, then divide by 12. This will give you your average monthly net pay over the 12 months’ you aren’t working and this figure can be your monthly budget for the whole year.

In the example given above, the average monthly net pay is £678.25. If you accept this as your sole monthly income for the first year, that should stop you overspending in the early months, when your salary is relatively normal.

| Month of leave | Net pay |

| 1 | £1,711 |

| 2 | £1,711 |

| 3 | £1,711 |

| 4 | £1,002 |

| 5 | £1,002 |

| 6 | £1,002 |

| 7 | £0 |

| 8 | £0 |

| 9 | £0 |

| 10 | £0 |

| 11 | £0 |

| 12 | £0 |

| Total for one year maternity leave | £8,139 |

| Average monthly pay over one-year period | £678.25 |

The first year of parenthood - some questions answered

Should you take shared parental leave?

Taking shared parental leave rather than one person taking maternity leave, which is likely to be more generous than statutory pay, will leave the majority of couples worse off financially unless the mother earns significantly more than the father.

That’s unless your employer offers an enhanced paternity pay package that makes taking shared parental leave more feasible.

Some large employers now offer paternity pay with full pay of up to six months and this looks set to be a trend.

If you want to take shared parental leave even though it will leave you worse off financially, you can do so – there are other reasons to consider it, after all - but it makes it even more important to plan ahead and save more in advance.

Do I still pay tax on maternity or paternity pay?

Yes, all your income is taxable, but if you are on a reduced level of income you are likely to pay less tax overall.

Can I still contribute to my pension?

Yes you can. The way it usually works is your employer contributions will stay at the same level as they were before you went on leave, but your contributions will come down according to what you are being paid.

Do I still have to pay student loan repayments?

If you are still earning over the threshold, your student loan repayments will still be deducted from your pay.

PAIN POINT 2: The cost of childcare

If there is one outgoing which consistently comes as a shock to new parents when they encounter it for the first time it is the cost of childcare.

It’s shocking because it’s difficult to grasp how it affects your finances until you are using it.

It’s shocking when you sign up to a day nursery and realise you pay for it even for days when you aren’t working.

It’s shocking when you realise that something called “free” hours for 3 and 4 year olds is not actually free at all. (We explain more about how much you can expect to pay even when your children are 3 and 4 later in this guide).

Not surprisingly, the childcare years are the worst from a cost perspective. The average full time nursery place for a child under 2 in England is nearly £1,000 a month, according to the Family and Childcare Trust.

The following table shows average childcare costs for full-time and part-time nursery provision depending on the age of the child:

| Cost of full-time childcare (nursery) England | £ Average yearly | £ Actual cost |

| Child aged 0 to 1 | £12,789 | £3,197 (if parent returns to work after 9 months) |

| Child aged 1 to 2 | £12,789 | £12,789 |

| Child aged 2 to 3 | £12,483 | £12,483 |

| Child aged 3 to 4 | £4,983 | £4,983 |

| Child aged 4 plus attending pre-school | £4,983 | £2,491 (if child starts school half way through) |

| Total anticipated outlay on full-time childcare in pre-school years | £35,943 (or £28,754 with tax-free childcare meeting 20% of the gross cost) |

The most significant across-the-board government support doesn’t kick in until a child turns 3, when you are entitled to funded hours from local nurseries either 15 or 30 hours depending on how much you work, and your income level.

However, for those on a low income, Universal Credit (or tax credits) can cover up to 85% of childcare costs. (Note that applying for Tax-Free Childcare while on Universal Credit will mean that your Universal Credit help with childcare is stopped).

| Cost of part-time childcare (nursery) England | £ Average yearly | £ Actual cost |

| Child aged 0 to 1 | £6,706 | £1,676 (if parent returns to work after 9 months) |

| Child aged 1 to 2 | £6,706 | £6,706 |

| Child aged 2 to 3 | £6,540 | £6,540 |

| Child aged 3 to 4 | £2,559 | £2,559 |

| Child aged 4 plus attending pre-school | £2,559 | £1,279 (if child starts school half way through) |

| Total anticipated outlay on part-time childcare in pre-school years | £18,760 (or £15,008 with tax-free childcare meeting 20% of the gross cost) |

The table below summarises the main sources of help with childcare costs.

Table: Different types of support for childcare costs1

| Childcare support | Age of child | Nation | Applicability |

| Funded childcare for 2 year olds | 2 year olds | England | 15 hours a week for 38 weeks a year for parents in receipt of benefits (including in-work benefits) or children who are disabled or looked after. |

| Scotland | 600 hours a year for parents in receipt of benefits (including in-work benefits) or children who are looked after. Eligibility criteria narrower than for English families. | ||

| Wales | 12.5 hours a week for 39 weeks a year for 2 and 3 year olds in Flying Start areas (geographic areas which are deprived). | ||

| Universal funded childcare for 3 and 4 year olds | 3 to 4 year old | England | 15 hours a week for 38 weeks a year for all 3 and 4 year olds. |

| Scotland | 600 hours a year for all 3 and 4 year olds (12.5 hours a week for 48 weeks). By 2020, all 3 and 4 year olds will be entitled to 1140 hours a year. At the moment this is being piloted in some local areas. | ||

| Wales | 10 hours a week for all 3 and 4 year olds. Increased to 12.5 hours for 3 year olds in Flying Start areas. | ||

| Funded childcare for 3 and 4 year olds with working parents2 | 3 to 4 year olds | England | 3 and 4 year olds with working parents are entitled to an extra 15 hours a week funded childcare for 38 weeks of the year, meaning they get 30 hours a week in total. |

| Scotland | No difference to universal funded childcare (above). | ||

| Wales | 3 and 4 year olds with working parents will be entitled to 30 hours per week for 48 weeks a year. At the moment this is being piloted in some local areas. | ||

| Tax Free Childcare | Aged under 12 or under 17 if child has a disability | All nations |

Covers 20% of childcare costs up to a maximum of £2,000 per child per year or £4,000 for disabled children. |

| Universal Credit | Any age with Ofsted registered providers | All nations |

Pays up to 85% of childcare costs up to £175 per week for one child and £300 for two or more children. This is set to replace Tax Credits and other benefits. |

One thing to bear in mind with childcare costs is that usually, for day nurseries, childminders and nannies, you pay for them even if your child is ill and cannot attend their setting, as well as if you are on holiday.

How to cut the cost of childcare

- Ask a relative to help out. This is by far the biggest money saver – the only catch is having a relative willing to help out not just for a few hours, but on the basis of your working hours. This can be a big ask for grandparents, but if you are lucky enough to have this willing support, it will save you thousands of pounds. You can also transfer your National Insurance credits to Grandparents who are no longer employed but looking after your children so you can go to work. Find out more about this scheme at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/looking-after-the-grandchildren-make-sure-it-counts-towards-your-state-pension.

- Use any support schemes available, such as Tax-free Childcare (https://www.gov.uk/tax-free-childcare) which offers a 20 per cent top-up from the Government to parents who meet the criteria. The Government also provides 15 or 30 hours funding, where the local authority part-funds the cost of childcare per hour depending on your working status, when your child is 3 and 4. The 15 and 30 hours offer is touted as “free” by the Government, but in reality, nurseries still require contributions from parents towards their costs, as they often don’t receive enough from local authorities to cover the costs of offering the hours totally free.

- Use a childminder rather than a day nursery –they tend to be about 10 per cent cheaper.

- Research and compare the costs of different childcare providers locally – they can vary dramatically depending on their status – and get your son or daughter on the waiting list for the one you want as early as possible, so you are not forced to accept a place somewhere out of your budget.

- If you are working or about to start work and on a low income, there is a childcare element to Universal Credit that you can claim – up to a monthly maximum of £646.35 for one child or £1,108 for two children. You can check whether you are entitled to claim here https://www.entitledto.co.uk/help/Calculating-Universal-Credit.

- Consider a nanny or nanny share if you are on a higher income when you have two or more children. Two children in day nursery is twice the cost. Believe it or not, it can work out cheaper to hire a nanny or better still, nanny share, than it is to pay for two day nursery places. Bear in mind though, that hiring a nanny involves paying their tax and National Insurance, as well as holiday, pensions and sick pay.

- Hire an au pair to help look after older children if you can accommodate an extra person easily (a decent size spare room and a separate bathroom to the one you use is usually expected). They can do the school run for you and prepare children’s meals. Expect to pay £80 to £100 a week for an au pair.

- Ask your employer about flexible work and work from home days. You’ll still need the childcare, but shaving two hours travelling time to and from work off the hours that you require childcare can cut hundreds a month off your bill.

NB. You might have heard of childcare vouchers – an employee benefit offered by some employers that offers tax relief on childcare bills up to £243 a month for a basic rate taxpayer and £124 a month for a higher rate taxpayer. They closed to new applicants in October 2018, so only those parents who already had them can still use them.

The inflexible nature of childcare costs can penalise self-employed mothers in particular, who might not be able to earn during holidays, or if their child is off sick (or they are) and they can’t work (these unexpected hindrances can occur on a regular basis with young children!)

PAIN POINT 3… more children

Decisions about how many children to have clearly come down to a lot more than finances, and yet, one of the reasons most often cited for not having a third child is that it will cost too much to do so3.

There is an argument that the more children you have, the lower the additional cost per child (because you’ve already got all the clothes and toys you need). That may be true, but there are also lots of costs that are unavoidably higher when you have more children, and the first of these is childcare.

The way support for childcare costs is structured, as we saw before, means that the most expensive phase is between the age of one (or whenever both parents are back to work), and the age of three, because government-funded hours do not kick in until the term after your child turns three (unless you are in receipt of tax credits, in which case 15 hours of free childcare starts at age 2).

This means that the closer together you have your children, the harder the costs of childcare will be to bear in the early years - although you may make more than that back by being able to return to full-time work more quickly.

From a purely financial perspective, having children further apart can mean that the cost of childcare, if this is a consideration for you, can be spread out. But of course on the flipside of that, having children at bigger intervals means an eventual return to full time work could take longer.

Cost-wise, the worst case scenario for working parents who have three children is that they have three children all under the age of 3, all requiring costly childcare. Full-time care for three children in the early years, without factoring help from schemes like tax-free childcare and 30 hours funding, would be £3,000 a month. Assuming all of them are eligible to receive tax-free childcare, the cost would be £2,400 a month – not an easy cost for all but the highest income couples to absorb and carry on regardless.

However by far the biggest reason that having more than one child affects your finances is the long-term drop in income.

The likelihood of mothers returning to full-time work goes down with each child, according to ONS data. In couples with two children, the mother is more likely to be working part-time than full time. In couples who have three children, the mother is more likely to not be working at all. This means that the more children you have, the less likely you are to go back to the full-time earnings you enjoyed before you started your family.

3 For those in receipt of benefits, it’s worth knowing that there are restrictions for people with more than two children. Since February 2019, it has been possible to claim Universal Credit if you have three or more children but your payment will not include an extra amount for your third or subsequent child, regardless of when they were born, unless there are special circumstances.

What benefits can I get to help with the cost of children?

There are some benefits available to most families with children, such as child benefit and others paid only to those on a relatively low income, such as Universal Credit or Child tax credit.

Child benefit

Child benefit is a social security benefit for parents. You get £20.70 a week for your eldest or only child and £13.70 a week for any additional children, up until their 16th birthday – or later if they stay in education or training. It’s a useful £1,788.80 a year for a family with two children who are eligible.

Whilst child benefit is payable regardless of income, higher income families receiving child benefit may find themselves with a tax charge as a result. In 2013, the Government introduced something called the High Income Child Benefit Charge, which requires those who earn more than £50,000 a year to pay a tax charge. If someone in the household earns more than £60,000, then the tax charge is equal to the amount of Child Benefit that the family receives.

Even if you or your partner earns above £60,000 and you don’t want to claim Child Benefit, you should fill out the form, as doing so will entitle you to National Insurance credits towards your state pension. Without these credits, you may not receive your full state pension entitlement when you retire because of gaps in your NI record for years spent at home with children.

Child tax credit

To get the maximum amount of child tax credit, your annual income will need to be less than £16,105 in the 2019-20 tax year.

If you earn more than this, the amount of child tax credit you get reduces. Various online calculators are available to help you work out how much you might get, including at www.which.co.uk and at www.entitledto.co.uk. You might also be able to claim working tax credit (see below).

The elements of child tax credit are:

- Child element. This is included for each child born before 6 April 2017. For those born afterwards, a child element is only included for two children or less, with a few exceptions for multiple births, or if your child is caring for a child.

- Child disability element. There is a rate for a disabled child, as well as a severely disabled child rate. Which one you get depends on the circumstances of the child in your care.

- Family element. Each family will be given one family element if there is a child or children born before 6 April 2017. This is not included if the child or children are all born after this date.

Working tax credit

The maximum amount is payable for those earning less than £6,420 a year. If you earn more than this amount, you lose 41p of the maximum amount for every extra £1 you earn. The minimum number of hours you have to work to qualify for working tax credit depends on your age, whether you are part of a couple, whether you are disabled and whether you have children.

To get a feel for the total amount you might get from child tax credit and working tax credit, the following table from the Which? website will give you some idea. Note however that tax credits are gradually being phased out and replaced by Universal Credit which has its own set of rules of entitlement.

| Household Income | One child | Two children |

Three children |

| £6,420 | £8,105 | £10,885 | £13,665 |

| £10,000 | £6,645 | £9,425 | £12,205 |

| £15,000 | £4,595 | £7,375 | £10,155 |

| £20,000 | £2,545 | £5,325 | £8,105 |

| £25,000 | £495 | £3,275 | £6,055 |

| £30,000 | £0 | £1,225 | £4,005 |

| £35,000 | £0 | £0 | £1,955 |

PAIN POINT 4: The long-term drop in income from reduced hours in work

You can usually predict a drop in income in the first few years. What’s harder to predict is the long-term drop in income that will occur.

The income drop – equal to approximately 20 per cent of household income for ten years.

It’s usual for one parent to take some time out of work when a couple has children. That’s partly because parents often want to be around for their young kids as much as possible. It’s also partly to do with the prohibitively high cost of childcare. Many parents find that they can’t earn enough after paying for childcare to justify going back to work.

For some, managing family life, the logistics of children's schooling, activities and social lives, means that even when the cost of childcare becomes less of a problem, income never goes back up to the level of two full-time workers.

Rather, until the youngest child in a family is 11, “the most common arrangement”, according to the ONS, is one parent (usually the father) working full time, while the mother works part-time. This is the set up for 49 per cent of families.

For mothers, the more children you have the less likely you are to ever go back to work full-time.

According to the ONS, where couple families had one child, both parents worked full-time in just over half of cases, compared with approximately one-third of cases for couples who had three or more children.

The following case study shows the long-term impact on your income of having children and going part-time.

Case study: Impact of lost earnings through going part-time after the birth of a child

Consider a couple on typical joint disposable income of £33,884 per year. Suppose that the mother moves from full-time to part-time work after the birth of their first child and remains part-time for the typical period of ten years. This reduces the couple’s disposable income to £27,107 a year. In terms of monthly income, that is a fall of £565 per month over a ten year period.

As well as a sustained drop in income, some other knock-on effects to think through are:

- Reduced retirement savings for the mother

- Reduced borrowing ability for buying a new home/remortgaging

- More stringent budgeting for general living costs

- Greater risk of going into debt if big expenses are incurred

- Possible loss of career progression for the mother

Buying a house when you have young children

Some lenders will take a more generous view than others, however, so using a broker can help, as they are likely to know which banks and building societies might, for instance, take into account how long you will be paying childcare costs for, or whether you receive free help from a grandparent.

Also be sure to declare any child benefit payments you receive, as these will count towards your income in the eyes of a lender.

If you are already a homeowner and want to remortgage or move, the same lending restrictions could apply, so it might be better to make any big changes before childcare costs arise.

PAIN POINT 5 – The school years

After school clubs and holiday clubs

The childcare costs have fallen, but activities, holiday clubs and before and after-school clubs are all still to contend with. Sending your children to a state-funded primary school does not mean never having to pay for anything again!

According to CORAM’s figures, the yearly cost of things like after-school clubs for working parents is about £2,200 – that’s for the 38 weeks of the school year.

For the remaining 14 weeks a year of holiday, it’s likely that parents will use their own holiday allowance to take care of their children during some of this time. Between two parents (one full-time, one part-time) this could add up to about five weeks, assuming some of that holiday time will be taken together.

So for around nine weeks, parents could find they have to pay for holiday clubs. These typically cost around £130 a week for 9 til 5 attendance, according to CORAM, giving a total annual cost of £1,170.

An annual budget for two children who are in school for working parents therefore comes to about £6,800, or about £567 a month.

Other costs

Shoes, uniform and term-time activities outside of school all add up, though some schools will help parents to find cheaper sources of things like second hand uniform.

These bills are sometimes termly, sometimes monthly, which can make it hard to budget. Expect to pay between £20 and £30 a month per child for each external activity they participate in.

Schools can offer help for parents who are struggling to meet costs of school-organised activities. All state-funded primary schools offer free school meals to all children until the end of Year 2. Beyond this, lower income families on tax credits or universal credit may continue to qualify for free school meals.

Holidays

By far the biggest bugbear of parents is the cost of going on holiday in the designated school holidays.

The cost of flights and accommodation can more than double in the school holidays – and it can be a big problem for parents on a tight budget.

Some parents choose to go on holiday during term time to save money, though this is increasingly likely to trigger a fine levied by the school.

This is a personal decision, but it’s worth looking at all of the ways to cut the cost of your holidays first before resorting to term time breaks and fines: going to stay with friends to save on accommodation costs, for example; or going on holiday with friends.

It’s important to consider the cost of any fine from school when you are working out what to do. These are usually levied per child, per day.

PAIN POINT 6 – Your children's future

Your children might not be dependent on you for many things when they reach 18, but the financial demands do not stop there. There are cars, university and first homes to pay for – even their pension savings - none of which are very affordable for those starting out in adult life on low salaries – as you probably remember too well.

It’s natural for parents to want to help and the best way to do so is to save a little bit from as early as is possible for each child – even if it’s just £10 a week.

£10 a week from birth to age 18 in a savings account paying 1 per cent would give a pot worth £10,000 by the time your child reaches 18.

While junior ISAs, with a limit of £4,368 a year, are a popular choice – with most parents opting for the safety of cash rather than the riskier (but potentially higher return) stocks and shares – you can also save for your child using your own ISA allowance.

The advantage of this is that unlike with a junior ISA, which your child will automatically be able to access for themselves at the age of 18, you can keep control of the money in your own ISA and make sure it is used for something important!

You can also pay up to £2,880 a year into a child’s pension, on which they will receive 20 per cent tax relief.

In the last section we looked at the financial ‘pain points’ that come with having children. In this section we offer some advice on how you can cope with this squeeze on your living standards.

Among the excitement, the decisions on names and nursery décor, finding the time to plan your finances in the run-up to your first child and for years beyond is, while less fun, absolutely vital if you are to deal with the ‘concertina effect’ on your finances.

The difficulty with this is knowing how to plan for it. Many new parents are shocked at how difficult it is to manage the higher outgoings associated with having a baby on a reduced income.

How difficult it is for you personally will depend on many factors:

- whether you are a single parent

- the generosity (or otherwise) of your parental leave payments from your employer

- whether or not you have an employer or are self-employed

- whether you are a homeowner or you pay rent

- whether you have your children close together in age (and therefore have two lots of childcare to fork out for at the same time)

- whether you go back to work

- whether you will have free childcare help from a relative or friend

- whether you live in an area where childcare costs are expensive

- whether your partner earns more than you

- whether your child has special needs or a disability

- whether you were already stretched financially before you had children

- when in the year your children are born

- how much your nearest nursery charges

- whether you are entitled to any benefits or tax credits

...the list of variables goes on.

But the rules below should help anyone planning a family work out how to navigate the financial changes to come.

Rule 1. Budget, budget, budget

To work out the kind of budget you will need to be on, check out pain point 1.

You need to work out what your income is likely to fall to once you have a baby, then work out what your new joint disposable household income will be, then add in a big new spending line: “BABY” to all of your other outgoings. As noted earlier, a working assumption of £8,000 per year or £666 per month is not a bad place to start, especially if you expect to have childcare costs.

If we take an example couple – let’s call them “Ben and Natalie” on the typical joint disposable income for their age of £33,844 – or £2,820 a month.

Before children, their outgoings look like this: rent is £833 a month – the average for a privately rented home in England, and they spend £400 a month on food. Other bills including council tax, energy, fuel, water and phones come to about £400 a month, so their basic living costs come to more than 50 per cent of their joint net income.

They are saving £300 a month towards a deposit, too. After these outgoings, they have about £900 left over for “discretionary” or non-essential spending on clothes, going out, holidays and other savings.

Here’s what changes with the arrival of their first baby:

Let’s assume that Natalie, who earns £25,000 a year gross normally, wants to take a year of maternity leave when the baby is born.

Her employer offers six weeks’ full pay, six weeks’ half pay and the rest is statutory pay - currently £148.68 per week. She will earn £9,827 for the year, or £818.93 a month (she wouldn’t pay tax on this income as it’s below the personal allowance threshold), compared to her normal net pay of £1,711.This means that

the couple have a disposable income £900 a month lower than normal – or about £1,900 rather than the £2,820 they are used to receiving, for this year. This is almost equal to the amount they usually have left over for discretionary spending – so they are only just in the black.

The problem, of course, is that their outgoings have actually gone up – by £333 a month (they aren’t paying for childcare yet). So they have to cut their other spending by about £300 a month in order to avoid going into debt.

The easiest costs to cut might be their energy, fuel, phone contracts and food bills – so making sure they are on the cheapest deals and shaving as much as they can off their food shopping could help with some of this.

It’s clear though, when looking at these figures, that the couple need to have some money saved up in advance to cover the shortfall in their monthly budget during Natalie’s year of maternity leave to avoid going into debt (we consider what a savings plan might look like below).

But in the next year, when Natalie goes back to work, budgeting gets even tougher as their outgoings go up again, because they begin to pay for childcare….

When Natalie does return to work, she goes back part time: three days a week. She is now earning £15,000 a year. Her monthly net salary is £1,144 a month.

So the household income is down by £567 a month – or 20 per cent - compared to what it was before they had the baby - but it is up on what they earned in the first year of their child’s life.

In order to work, Natalie is paying for part-time childcare, which costs her £128.98 a week – or £558 a month. A combination of new costs (childcare) which they didn’t have before and reduced income from Natalie working part-time has wiped out all of the discretionary cash that they had each month – and they have little spare cash to cover any emergencies, such as boiler or car breakdowns.

Summary: How to budget

- Know what you have left to spend after all essential outgoings

- Try dividing your monthly discretionary amount by the number of days in the month to give you a rough daily spending limit

- Keep a regular, monthly check to record any ups and downs in spending

- Shop around for the best prices on phone and broadband bills, TV packages, utility bills, insurance costs etc., and always challenge any renewal quote you are offered by ringing up to see if a better deal is available.

Rule 2. ANTICIPATE future work and life goals

Try to work out how likely it is that you will go back to work full-time and when, based on what you do know, such as your employer’s attitude to flexible working, how much you earn and how long you will be paid during parental leave. Whilst you can take the full first year off work, statutory maternity pay (to which you may have a legal right) ends in week 39 – so if you take the whole 12 months off you probably won’t be earning anything for the final three months, unless your employer’s scheme is unusually generous.

It’s also important to consider how you think you will feel about returning to work – emotions are not straightforward when it comes to taking your baby or toddler to nursery or a childminder for the first time and it’s good to keep your options open if you possibly can, rather than feeling forced to return to work. If you expect you won’t want to rush back, then budget and save more so that you can accommodate this plan.

Also think about any other big costs that are likely to crop up in the next few years, such as a first home purchase. Maybe even a wedding, if you aren’t married yet but think you might like to.

Think about how all of the costs associated with having children might affect these plans, too. For example, if you are saving into your family fund, how much if at all are you prepared to eat into the home deposit savings? Are you happy to delay a wedding for a few years or perhaps do it on a budget? It will be hard to save for a large number of expensive life goals simultaneously so some prioritisation is a good idea.

Rule 3. PREPARE and do your research

1. Pay whilst you are off work for the first year

Check through your employer’s parental leave policy and pay arrangements. As explained earlier, these vary dramatically from little more than statutory pay to generous year-long pay packages where your employer continues to pay you your whole salary for almost the whole duration (although this is rare).

You should also check your partner’s parental leave package, as this will affect your choices in that first year. You should be able to take shared parental leave, as this is a benefit to all new fathers now, for the first 50 weeks. However statutory shared parental pay, like statutory maternity pay, is minimal at £148.68 a week in 2019/20 and is paid for 37 weeks rather than the 39 weeks of statutory maternity pay entitlement.

Paternity pay packages usually offer two weeks of fully paid leave to new fathers, followed by the statutory rate for any shared parental leave taken by the father after that up to 37 weeks – this is less generous than the enhanced maternity pay that is usually offered

to mothers.

For that reason, most couples still find it most economical for the mother to take more time off to look after the baby rather than the father. BUT (and it’s a big but) some large employers are improving their paternity pay to bring it into line with pay for mothers.

If more employers do this, it will become feasible for more fathers to take time out to look after the baby in that first year and couples will have more choice.

Top tip: One thing to consider is saving up any holiday entitlement you have during the year you are pregnant and adding it to your parental leave, to give you more paid time off, although you obviously need to look after yourself before the child is born and take proper time off.

2. Other things to prepare for – where you will live and who will look after the children

It’s a good idea to prepare for even further ahead than the first year, if you can. For instance, are you in the catchment area for local primary schools? This is more of an issue in some areas than others. It might sound crazy to think about something like that before you’ve even had children, but if you did decide you wanted to move, you might prefer to do it before children arrive on the scene. And you might want to avoid having to move twice in order to get into your desired catchment area and having to pay extra stamp duty.

It’s also a good idea to sound out relatives who might want to help with childcare well in advance, and to make sure any arrangement involving them is clear to everyone involved. The last thing you want is to plan to return to work on the basis of free childcare from grandparents, only to find they meant one day a week, not full time.

Rule 4. SAVE while you can

Your costs and income level are likely to vary a lot over the first few years of your children’s life and if you’ve both been comfortably managing on your joint income in the years before children, suddenly struggling

to manage can come as a shock. Childcare costs in particular, at around £1,000 a month on average for a full-time place for a child aged 1 or 2 (although it does tend to fall after that) can be tough to meet.

Saving as much as you can before the concertina effect of higher costs/lower income kicks in will give you breathing space later on.

If you like the “jar” method of saving, where you save for different purposes in different jars or pots, like Christmas, holiday, house etc, then starting a “family” savings fund, which is specifically for this purpose, is a good idea.

How to start a family fund for child one

If we take the average annual cost of a child through its life to be £8,000 a year, this works out at £666 a month.

It will be far easier to save this money out of your joint disposable income before you have your first child than it will be to try to pay your new child-related costs out of a diminished disposable income once they are born.

Where to put your savings?

Consider a regular saver attached to your bank account, if your bank offers one, as these can offer more generous interest rates. You want to be able to access your money when you need it. Generally, interest rates on instant access accounts tend to be lower than those that tie your money up for longer.

...saving on the spending

It’s hard to avoid spending on baby things. But when it comes to buying the things you need, if they are rush purchases, you are more likely to spend too much. Scour NCT sales, local Facebook groups and willing friends’ attics for much cheaper items.

Most parents would agree that buying new toys and clothes for their babies and toddlers was a huge waste of money, as second hand items are often hardly used and in good condition, for a fraction of the price.

It’s a lot to take in, but…

Having children is an expensive business and it is worth putting some thought (and savings) behind your family financial plans, to give you time and space to focus on the important things - like enjoying time with your children.

About 1.4 million people become parents every year – and most will somehow manage through the toughest times. In the end, how you get through will depend on luck, such as the parental leave offered by your employer, as well as judgment and planning. Your work, childcare and support patterns can change a lot over the early years and before you know it, financial pressures are not the worry they might have been at the beginning.

If you can get through the pre-school years without too much pain, you’ll have done the hard bit and that concertina should start to expand again.

Good luck!

For more information about Royal London or this report please contact:

Becky O'Connor - Personal Finance Specialist

Email - rebecca.oconnor@royallondon.com

All details in this guide were correct at the time of writing in June 2019